Back in January 2023, it was announced that John Akomfrah would represent the UK at next year’s Venice Biennale, and when we speak over Zoom in late April, the artist and filmmaker is in the city on something of a reconnaissance trip. Though Akomfrah has had time to let the news sink in, the announcement was something that could have blown him away. “Anybody who tells you that they’re not absolutely over the moon about being chosen for something like this, is lying. Because it’s great!” Akomfrah will be taking charge of the British Pavilion for the Biennale’s 60th edition, and it’s an opportunity that he says, “feels important in one really significant respect. It’s like someone has said to you, “We’ve watched what you’re doing and we’d like you to come and do the same again in this setting – one of the biggest settings on the planet.”

Next year won’t be Akomfrah’s first encounter with the Venice Biennale however; his three-channel installation, Vertigo Sea first premiered there in 2015, as part of the All the World’s Future exhibition curated by the late Okwui Enwezor, while another three-channel piece, Four Nocturnes, was shown at the inaugural Ghana Pavilion in 2019. And as much as the British Pavilion represents one of the biggest stages in the art world, Akomfrah intends to approach the task in much the same way he would any other work: “The project is the process, and the process is the project,” he says. “I’m here now, and I’m not doing anything different to what I would normally do. You just commune with a space, and ask it what it wants and it hasn’t quite told me yet!” At the time of our call it’s his final day in Venice, though Akomfrah will return to Venice at a later date to get a sense of what the space has to say.

Searching for voices that resonate and communicate with Akomfrah is a defining element of his work. Since the early 1980s, when he was working with the Black Audio Film Collective, the artist and filmmaker has been drawn to the sounds and stories that reach out for archival and found footage. The collective, formed by a group of students at Portsmouth Polytechnic in 1982, produced a number of documentaries, films and tape slide works that sought to grapple with Black British and diaspora identity, as the children of immigrants to the country in the post-war decades (Akomfrah moved to South London from Accra as a young child).

Handsworth Songs (1986) is one of the collective’s defining works. Part-documentary, part-montage, it examines the aftermath of “riots” occurring in Birmingham and London in 1985. It’s a documentary inasmuch as it presents footage shot by the collective on the ground, but equally, by drawing on archival footage, newsreel and still photography, Handsworth Songs is also an exercise in searching for something that wasn’t visibly, or physically, present at the scene. That’s to say that the collective were searching for the ghosts of the past that were haunting Birmingham in the mid-1980s, while also giving those same ghosts a voice.

The approach taken in Handsworth Songs was shaped by the work of the late cultural theorist, Stuart Hall – someone whose ideas, Akomfrah says, the collective and others working in the Black art movement in Britain at the time sought to emulate. From the early 1960s on, Hall was a defining figure in the emerging field of cultural studies, and his writing on identity (and in particular defining a sense of Black British identity) remains central to this day. This provided the framework, then, for the Black Audio Film Collective’s approach. As Akomfrah explains, “we understood this place [England], but we also understood the elsewheres that our parents came from; I knew London, but I also knew Accra – and these Janus-faced features of your life seemed to suggest that you needed a very unique kind of person who might tell you about this double-faced, double consciousness. And Stuart was that – he seemed to understand the racial dynamic that was powering our lives, and he understood the class dimensions of that.”

Hall was also a well-placed figure to help contextualise what the collective sought to achieve with Handsworth Songs; it had been in Birmingham where he had co-founded the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies in 1964. “And so in a very real sense,” Akomfrah says, “he watched the evolution of the kids [who were later in Handsworth in the mid-1980s]: he was there when they were born, he saw them going to school.” The collective approached Hall for his guidance on Handsworth Songs, and though he didn’t agree with everything they were doing, Akomfrah says, that was something that they appreciated – support and guidance (Hall famously defended Handsworth Songs from criticism by author Salman Rushdie in the letter pages of The Guardian).

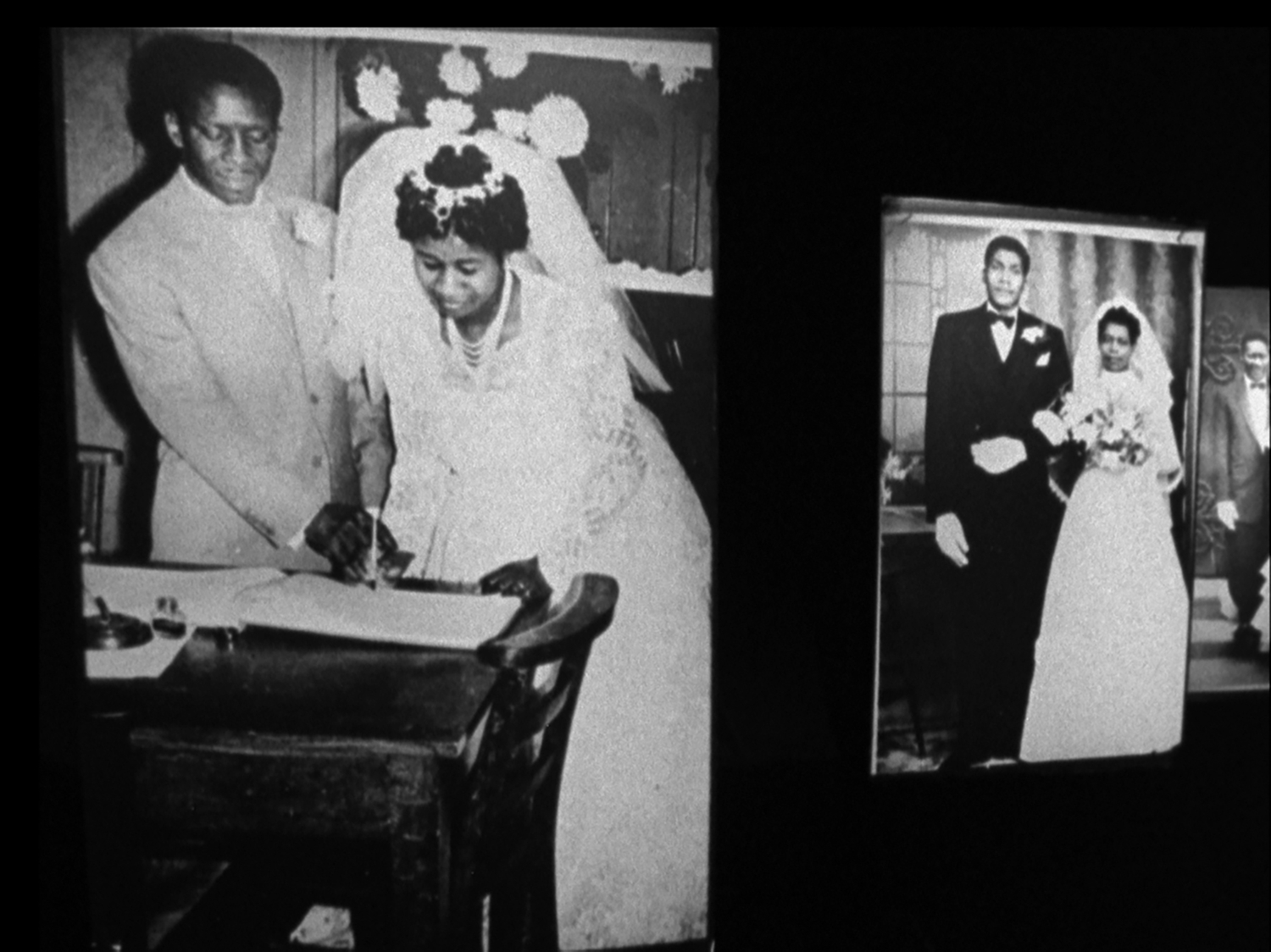

After the Black Audio Film Collective was wound up in 1998, Akomfrah went on to found the Smoking Dogs Films production company with Lina Gopaul and David Lawson, who were also members of the collective. Through Smoking Dogs, Akomfrah worked directly with Hall on two works that explore the cultural theorist’s life. The first, The Unfinished Conversation (2012), is a three-channel video installation that situates Hall’s ideas within the wider cultural and political landscape of the time through a montage of footage. The Stuart Hall Project (2013), a feature-length documentary soundtracked with songs by Miles Davis, is more introspective; though it broadly follows the same structural narrative, it emphasises how this titan figure in twentieth-century cultural theory was himself shaped by the environments he sought to understand. While Akomfrah mourns the loss of a friend and collaborator (Hall passed away in 2014), he notes that it would be “interesting to see what an equivalent figure – younger, more agile, more mobile – would be like in the present.”

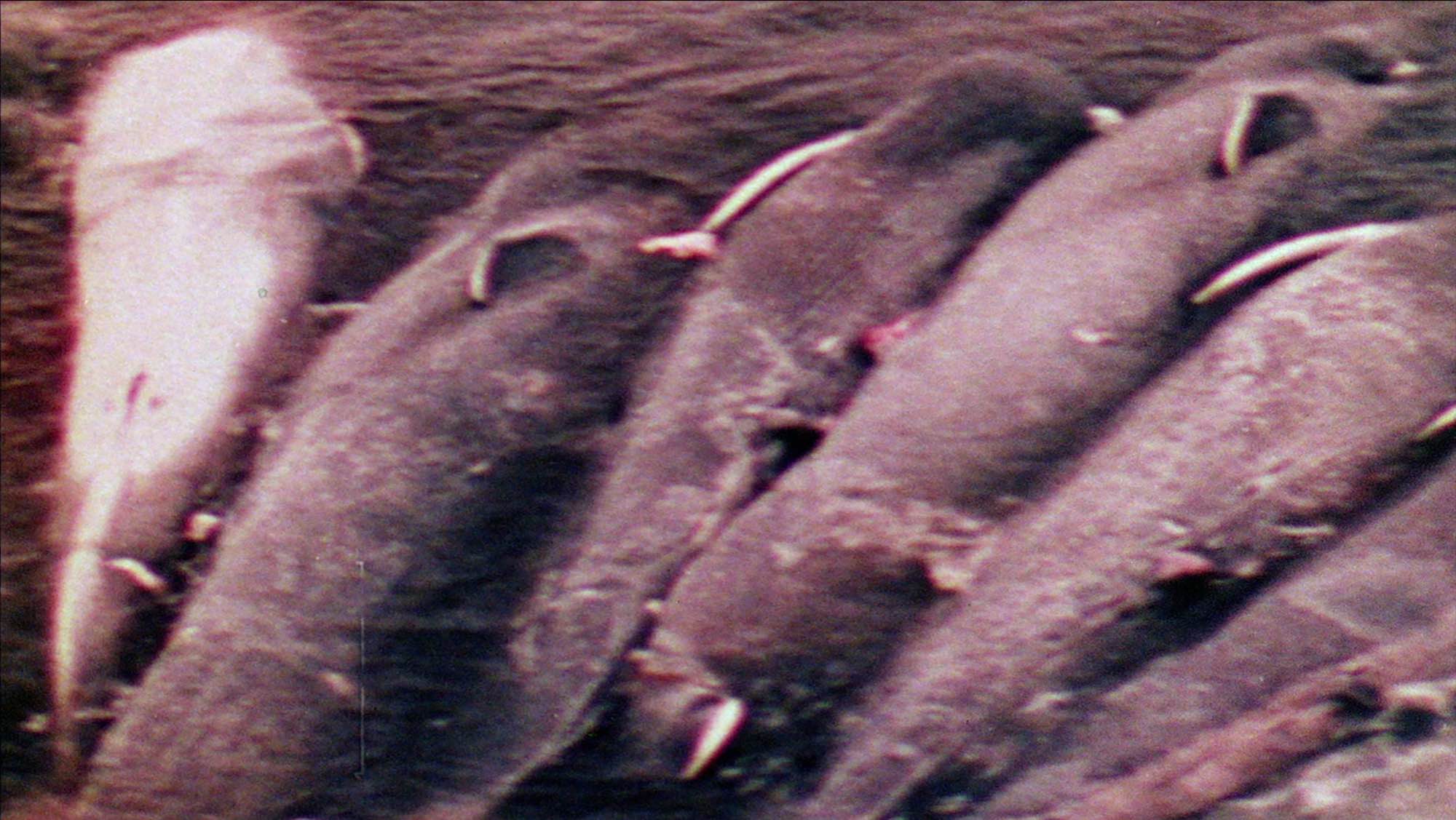

Over the past decade, Akomfrah has created a trilogy of multi-channel works starting with Vertigo Sea and ending with Four Nocturnes, that examine histories of migration through the natural environment. Vertigo Sea takes something of a metaphorical approach (relating, for example, the whaling industry to slavery and colonialism), in which the ocean is both central to the planet’s ecology and the setting for institutionalised cruelty and brutality. The second of the series, Purple (2017), is a six-channel installation commissioned for the Barbican’s Curve Gallery, and co-commissioned by the TBA21—Academy; the Bildmuseet Umeå in Sweden; The Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston; the Museu Coleção Berardo, Lisbon and the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow. It is Akomfrah’s largest work so far – both in terms of scale and focus. As a step further into the artist’s investigation into the environment as a linchpin for human life, Purple is an immersive portrayal of how climate change is impacting the planet told through a montage of footage – archival and new – that examines the uneven experiences of the Anthropocene.

Though the explicit subject matter of Akomfrah’s work has shifted over time, the ideas that define his oeuvre are largely unchanged. Indeed, even the images he draws upon reappear in different contexts. In Handsworth Songs, a brief black and white clip of a Black man working in a factory is seen, sandwiched between an audio clip warning of the threat to Britain’s national identity caused by an “army of total strangers – immigrants” which is reaffirmed by another clip of Margaret Thatcher speaking of the fear posed by the “swamping” of the country. This same clip reappears in Akomfrah’s later film, The Nine Muses (2010), an examination of post-war migration to Britain which foregrounds the journey of migration through the lens of Homer’s Odyssey.

At one point during our conversation, Akomfrah neatly surmises what it is I am getting at with the questions I put to him, as the “hangovers and overlaps between projects.” Those overlaps, Akomfrah acknowledges, remain unspoken by him. In much the same way that Akomfrah gives form to the ghosts of the archive that reach out to him, the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale will afford the filmmaker and artist the chance to communicate the ideas that have defined his work to date.

Of course, it should have struck me then that, if we were saying that the present was overdetermined by all sorts of traces and residues of the past that, at some point, we would also become part of the past. But it never entered my head to be honest – I mean frankly, it shocks me that the work is as old as it is. It feels like it was yesterday. I think it’s the inevitable logic of the position taken by Handsworth Songs that, at some point, it itself would be rendered phantom-like; that it would hover over the present in pretty much the same way as the discourse that we were trying to talk about. From the [start of] the Black Audio Film Collective in ‘82, we were fascinated by ghosts, or the ghosting process by which events are kind of hollowed out by the historical present day. There were small things that seemed to suggest that there might be unseen guests, if you like, sat at the tables of our lives. We’re all working with these unseen guests: the person clutching their handbag or the old man moving away from you has certain presuppositions – let’s call it that. And those presuppositions clearly had origins elsewhere, other than in the present. The logic of Handsworth Songs was this archaeological logic of seeing how many narratives that were overdetermining the quote-unquote “riots” at the time [in Handsworth and London] one could track back [into the past], and how far back one could trace them. And it seemed in the process of doing that, that quite a lot could be traced quite far back. They were not always necessarily bad things – that was the point of Handsworth Songs. We wanted to understand the kind of utopian dimensions of that present as well, because of course everybody who is on the streets revolting, in both senses of the word, was a product of some kind of utopian moment.

One of the important strands of Handsworth Songs was its attempt to understand the process by which, by the time Thatcher and that new right project gets going in ‘77 – ‘78, race [was being used] as a sort of mirror for the multiple crises of Britain. And, of course, there’s a striking resonance of that theme in the present, in the ways in which certain politicians are beginning to use that again. Vertigo Sea [came] at the time when journalists, certain right-wing journalists, were talking about migrants as cockroaches, vermin, and people who had these invasive, parasitic qualities to them. And I thought, “that’s interesting – how do we wrestle with this?” Because in order for the migrant or the refugee to be completely accepted as a problem (not even a person but a thing) you have to hollow out the actual reality of refugeeship and migranthood. The thing you have to get people to forget is the utopian quality of migrantship and refugeeship, because nobody leaves their home to go anywhere with the intention of being a problem. People leave because they think they’re going to go somewhere and make a contribution, not just for themselves, but to where they’re going. There’s a massive amnesiac machine at the heart of the anti-refugee, anti-migrant rhetoric, which is built on forgetting certain very, very positive things. And that for me is the most important thing to bear in mind. That’s why we started Vertigo Sea to say, “Look, these things were started at the same time: hunting for whales, for oil, and hunting people, for enslavement, have a joint history. And they were both incredibly profitable.”

In some ways, the relationship between cinema and the screen, audience and viewership, is really quite specific. The screen says, “I am this portal and I can be planted anywhere,” and you have a relationship with that portal. In a way, the environment doesn’t matter because it’s a didactic one between you and the screen. I think most gallery work says almost the exact opposite in a way, [where] the space in which the image announces itself is important. It does believe that, somehow, the relationship between screen, environment, character matters (though that’s not to say that you want that relationship to be prescriptive). The work is animated by a series of democratic impulses, which are very important for me: one is that you should be able to absolutely loathe it [laughs], and not think it has any value at all. Providing you’ve spent the time with it, that seems to me a takeaway that you are perfectly entitled to walk away with. You are absolutely entitled to say to yourself, “I’m only interested in what’s taking place in the middle screen, or the third screen; I’m not really interested in any of this stuff because there’s something there that I can follow.” Equally, if you thought that, especially with the multi-screen pieces, that there’s a sort of conversation between them that you’re interested in, fine. It’s an engine of empowerment, and your agency is important. I really do like it when people from different parts of the world write to me about their experiences, even the negative ones. You think, “Okay that’s great”, because at least they’ve turned up.

Handsworth Songs is playing at MoMA in a show called Signals at the moment. And the question of location has now taken on an additional quality that I think is really important to follow because it isn’t just about the space it’s also about what [people] can get out of it. MoMA wanted to do a closed-caption version of Handsworth Songs – because if you’re hard of hearing, the overly auditory quality of the film might not necessarily be to your taste. So, if people can plug into the film in a slightly more intimate way than just standing and watching an image, let’s do that. Let’s enrich that location.

There was a point when it became clear to a whole group of artists, not just the Black Art Collective, that we needed to understand our collective past. We needed to understand the ways in which our lives have been shaped by the past. We wanted to decode it because there’s a kind of impossible fiction at the heart of race – an impossibility about how it works. The present of race wants to deny that it has any efficacy, but it’s clear by the aftereffects of one’s feelings that there is a sort of elsewhere dimension to it. So part of the attempt to demystify this rhetoric of race (which says the past is unimportant, when in fact it’s quite clear that the past is central to the present) was to try and find ways to render intelligible the processes which seem to narrate the present. And the archival, both as a repository of the past, as well as a kind of embodiment of the past, seemed important. There are traces, residues and aftershocks that the archival, both as a repository and an embodiment, comes to stand for and is standing for. It was important to get to grips with that – obviously in different ways, because one of the things you reminded me of is the becoming archival of the practice itself! When you’re in your 60s and you’ve been doing this since your 20s, you also leave a trace and a kind of pathway. But I’m not following it, I’m just doing it – I’m not concerned about what the pathway is.