00.00

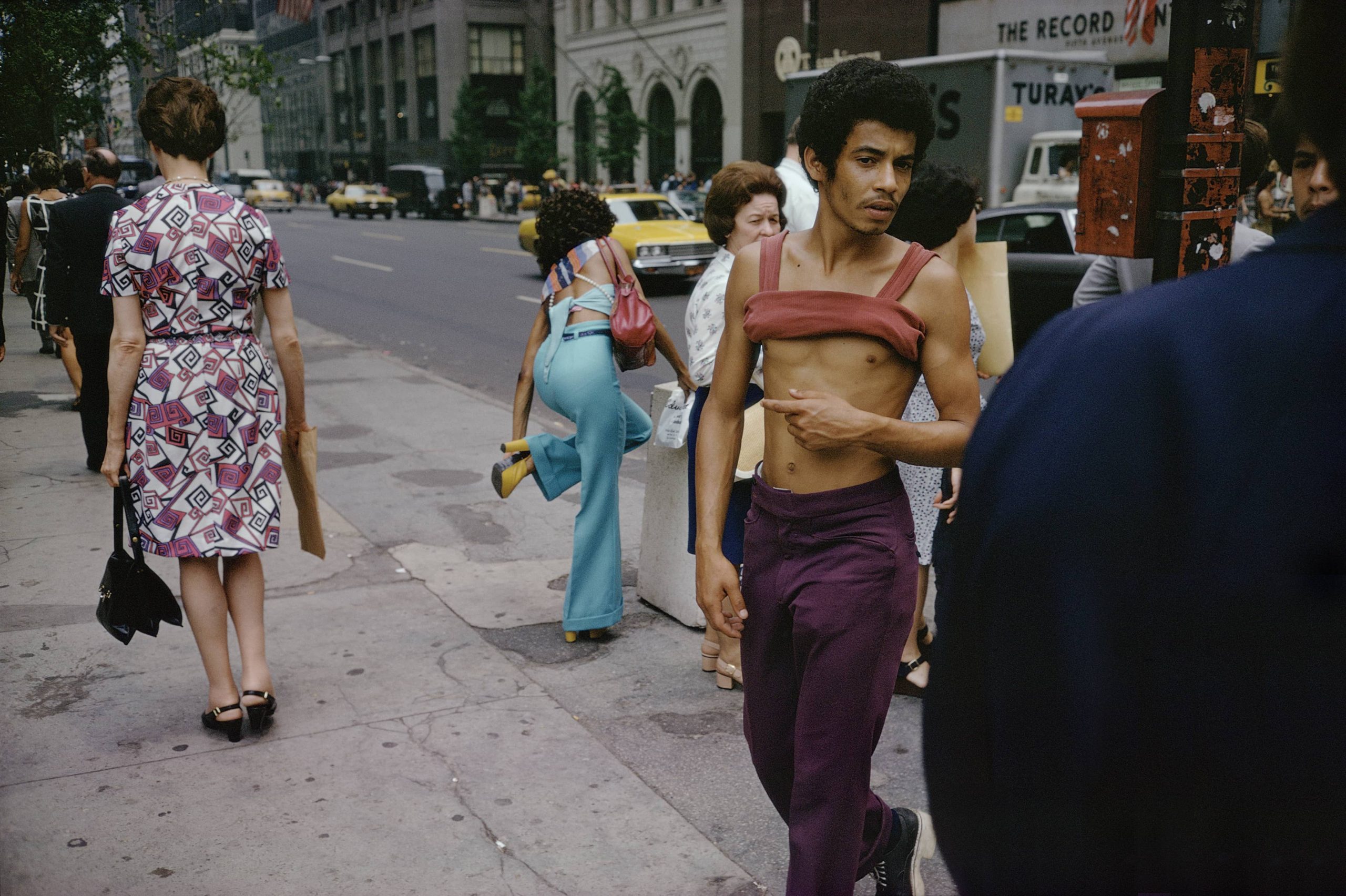

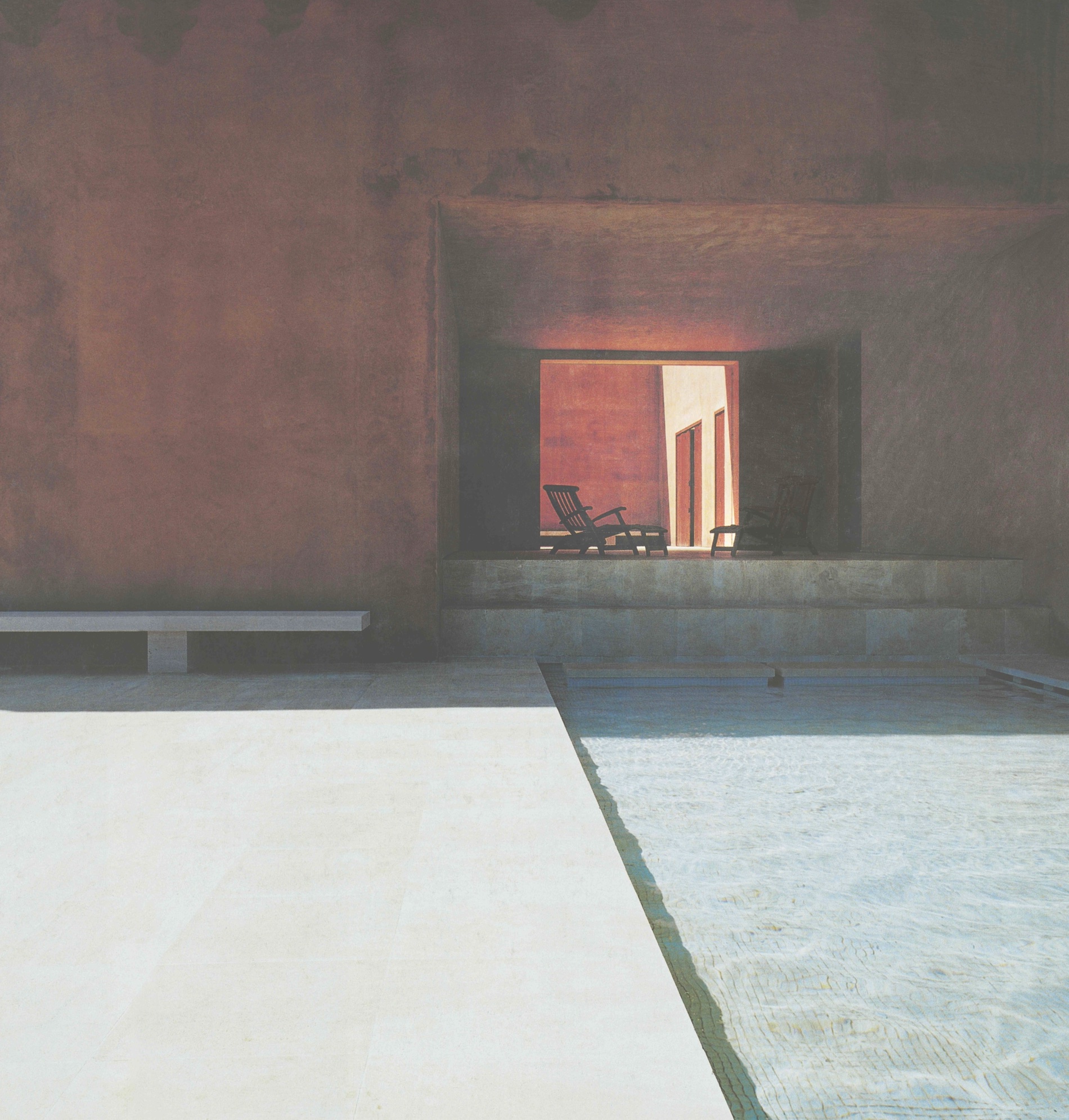

Pedro Reyes, Mexico City

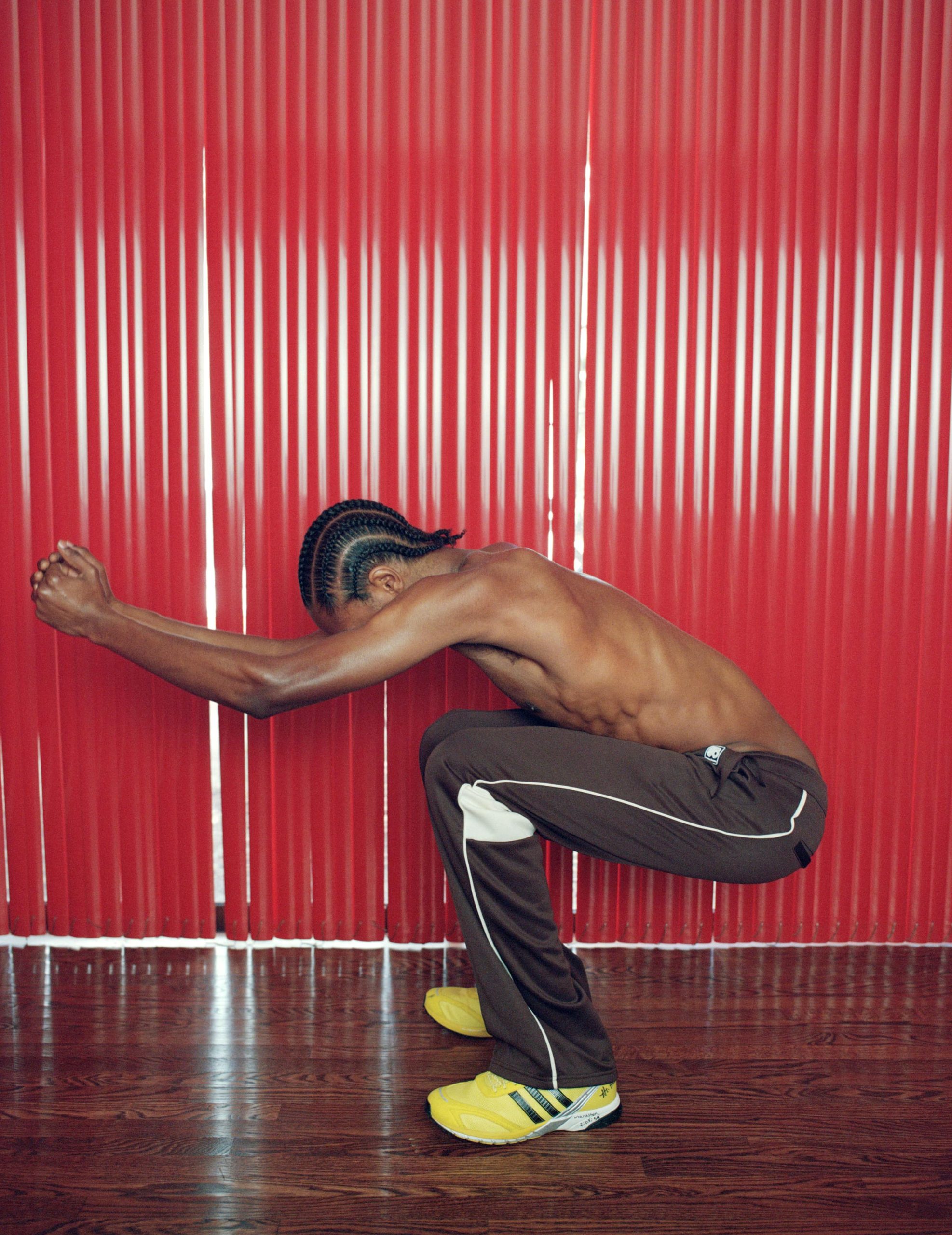

Present Space introduces HOME, its third print issue. HOME goes behind the doors of artists’ home and work spaces to see how they use their environment as a source of inspiration and space of creativity.

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Present Space is an independent film and art platform bringing together artists globally to create, connect and ignite conversations.

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More

Read More