Speaking over Zoom from her New York apartment, Dara Birnbaum describes her first encounter with video art as being either “by accident or fate” while living in Florence in the mid-1970s. She had come across Centro Diffusione Grafica, where a video work by the American performance artist Allan Kaprow was being shown in the back of the gallery. It struck a chord. Maria Gloria Bicocchi, the gallery’s owner, encouraged artists to make video art, and it was through subsequent visits to the space that Birnbaum met artists from both Europe and America who were in its orbit, including Dennis Oppenheim, Vito Acconci, and Dan Graham.

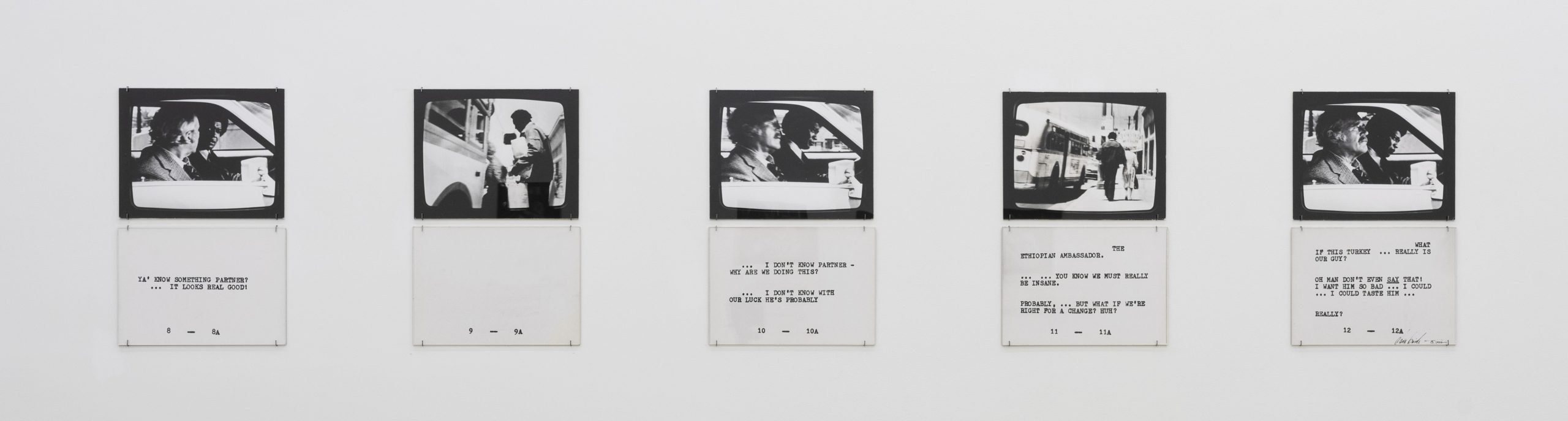

Returning to New York in 1975, Birnbaum began experimenting with video, though it was only when the opportunity arose to show at Artists Space gallery in New York City in 1977 that she would start “appropriating” television programmes. For the work in that show, Lesson Plans (To Keep the Revolution Alive), Birnbaum took photographic stills from Police Story and basically other weekly primetime crime programmes and presented the images alongside the dialogue from each scene. In doing so, Birnbaum laid bare the ideological and political underpinnings of innocuous seeming television dramas, in which derogatory language with racist undertones or sexist assumptions are uttered offhand. “That kind of speech,” Birnbaum says over Zoom, “is passing by so quickly: you’re looking at the action, you are not always aware of what you’re hearing.”

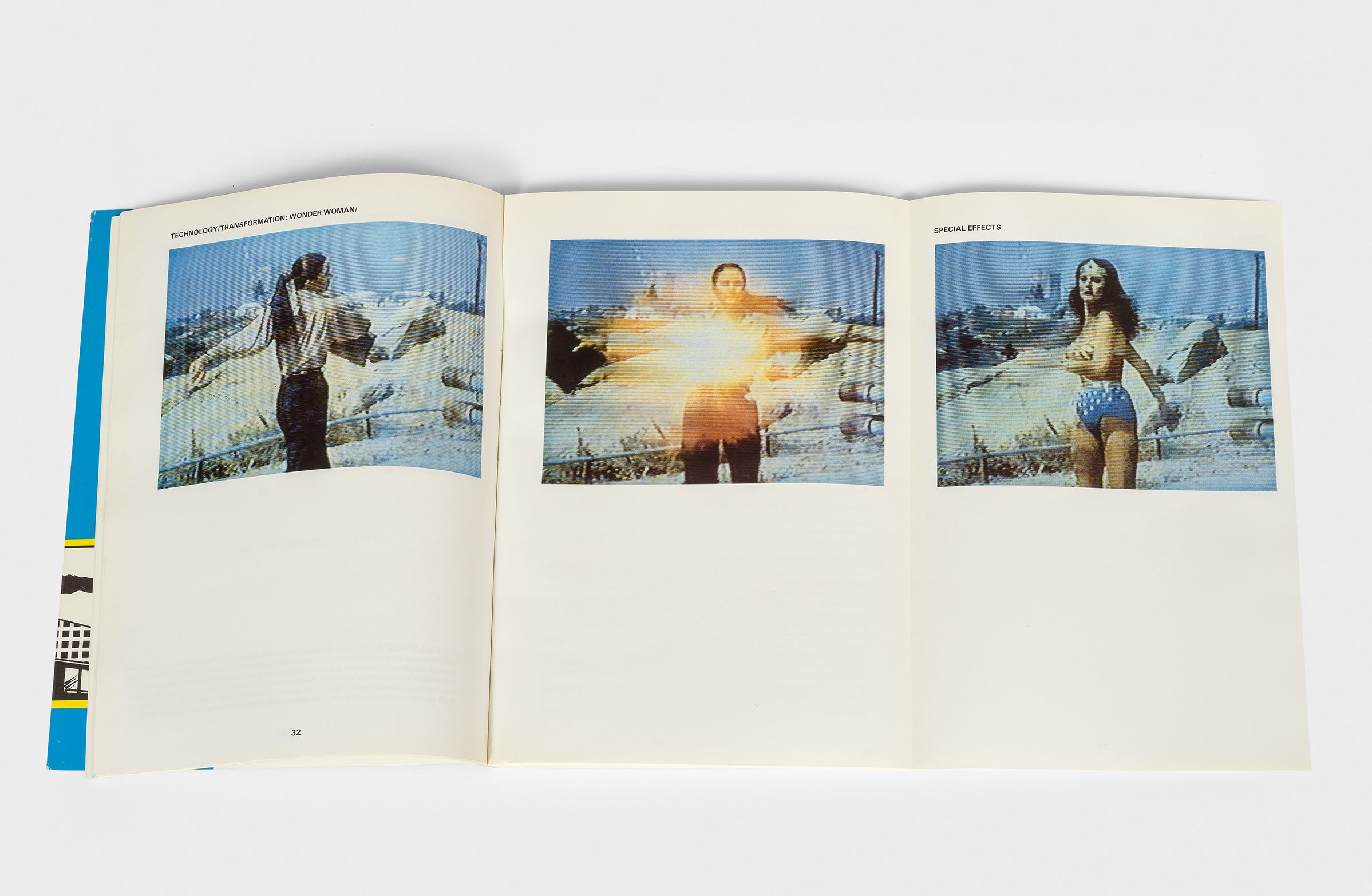

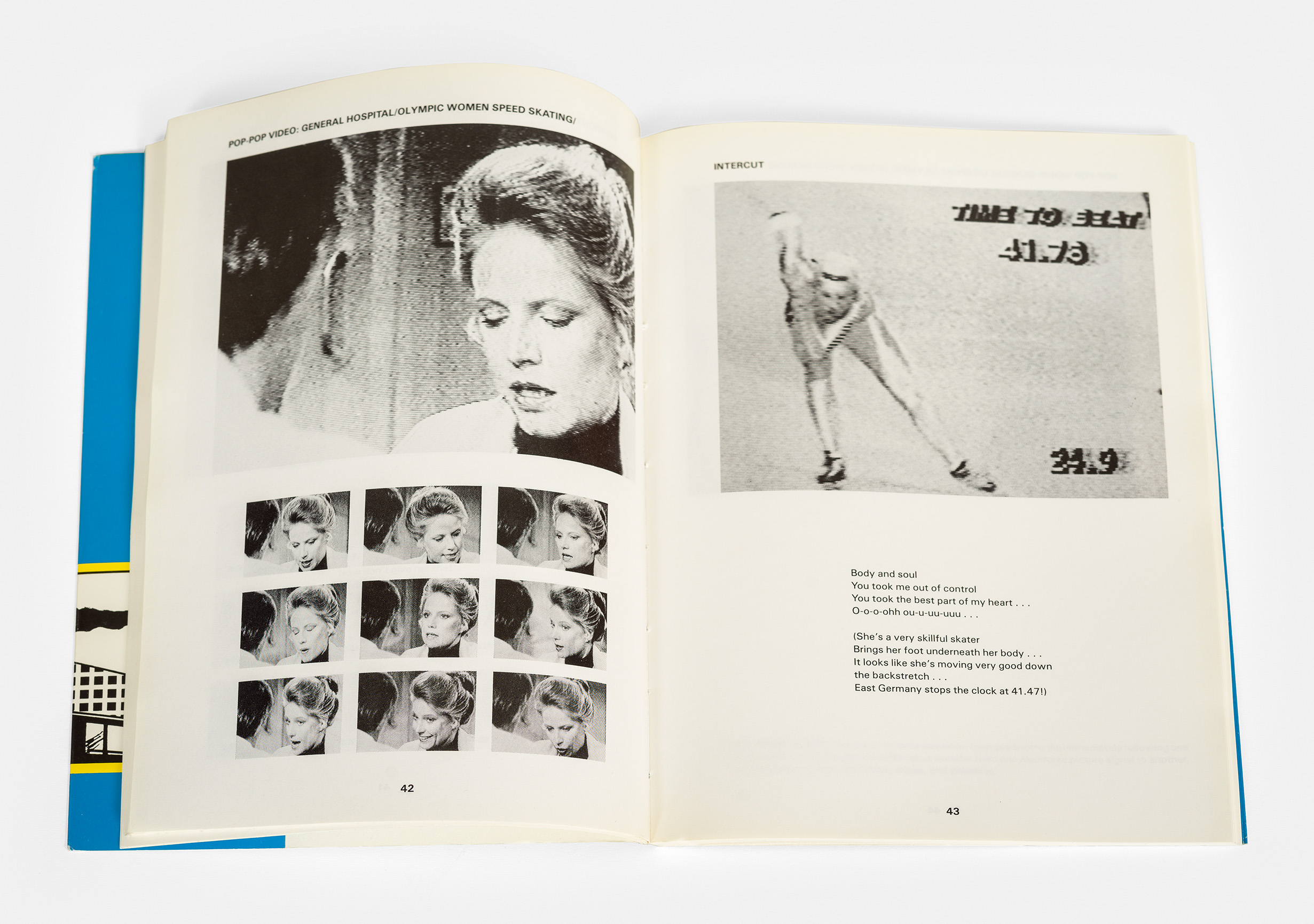

Birnbaum would continue to draw on television programming, though her method of doing so shifted from taking photographs off the screen, as had been the case with Lesson Plans, to using actual footage from shows like the sitcom Laverne and Shirley and Wonder Woman. The latter became the basis of Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978–1979), in which Birnbaum used clips of the titular character spinning repeatedly as she transitions from Diana Prince, secretary, into her superhero alter ego over some six minutes. In the introductory essay to the 1987 monograph Rough Edits: Popular Image Video, Birnbaum describes how, without the overarching narrative structure, the character of Wonder Woman becomes “flattened like a comic book layout. She runs, she spins, she saves a man, she runs, she transforms, and you’re left with, what I think is, the distilled essence of the program.”

Technology/Transformation was played on a Manhattan-based cable channel to coincide with the “real” Wonder Woman television programme, and it was also later installed to play on a TV monitor in the window of H-Hair Salon de Coiffure in SoHo, New York City. For those who inadvertently found themselves watching Technology/Transformation, they might recognise, as Birnbaum says, “something familiar: ‘Oh, look it’s Wonder Woman. Why does this turning and spinning never end?’” Ever since Lesson Plans the artist received feedback on the impact that “stopping the action” had on viewers: they “were startled that that’s what they’re looking at.”

Over time, Birnbaum’s work took on an increasingly political dimension, while continuing to investigate how what we view on television shapes how we see the world at large. Tiananmen Square: Break-In Transmission (1990), for example, is a five-channel piece that investigates coverage of the 1989 protests in China as they unfolded. A hidden surveillance switcher randomly cuts and switches what is shown on four of the channels, while also assembling and reassembling footage on a larger wall-mounted monitor, to evoke how television news reports on different aspects of an event, while purporting to broadcast the “true” event in real time.

While Tiananmen Square was envisioned for a gallery setting, Birnbaum has also experimented with public artworks. Between 1987–1989, the artist worked on Rio VideoWall, a permanent installation located at the Rio Mall in Atlanta, then a prominent shopping and entertainment centre. Video recordings of the site before the mall was built were screened on a wall of 25 assembled digital video monitors, while the silhouettes of shoppers cut a hole in this footage through a luminous activated keyhole that was produced by surveillance cameras at two main entry points within the site. By blocking out the landscape footage, the cut-out silhouettes of shoppers revealed live CNN newscasts, received through downloading satellite footage. The work was plagued with issues from early on, as the manager of the mall’s development attempted to appropriate Birnbaum’s installation and instead broadcast live sports and similar spectacle events. By 2000, the mall had been demolished and redeveloped.

In a way, the unintended consequences of Rio VideoWall fit neatly within the kind of critique that Birnbaum has offered since the inception of her career. Like television, the mall was a product of a post-war American dream, where the family at home and in everyday life were versed in the workings of a consumer culture. The roots of this are the subject of Birnbaum’s most recent work from 2022, Journey: Shadow of the American Dream, commissioned by, and included within, a survey of her work at the Miller ICA, the art gallery of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

Born in 1946, Birnbaum was herself a part of the first generation to grow up in the throes of the post-war American dream and its technologies, from home movies to television. In Journey, Birnbaum presents home movie footage of her young self, taken by her father, which is surrounded by five monitors that show clips from the television programmes she watched as a child. The roots for a piece like Journey are evident throughout Birnbaum’s extensive body of work, in which the artist has looked into the television screen to investigate how we are shaped by what we see, as seen through the long-cast shadow of the post-war consumer dream.

I had moved from New York City to Berkeley, California in 1970, at a time when it was very radicalised. And I think that in my heart there has always been a desire for change and for a confrontation in the sense of being able to talk back to the media, and maybe also to talk more generally about things that were happening at the time. Dan Graham, who became a friend and mentor, lent me an issue of Screen magazine out of England. It did not speak about television, [but] I thought television seemed to be the most important popular language at that time in the United States. And as I came to this realisation, in around 1977, when the Nielsen ratings here were saying that the average American family was watching television for some 7 hours and 20 minutes a day. I thought that was pretty startling and I felt that there needed to be this way to talk back, talk about, or uncover—if you’re watching 7 hours and 20 minutes a day—what is really being said.

So, the first work that was done with what as a strategy is now called “appropriation”, in this case of television, such as in Lesson Plans (To Keep the Revolution Alive) in 1977. At that time, we did not have any home technology like VHS or Betamax to record from television. So, I shot Lesson Plans with a 35mm camera pointed at the TV screen, as I was also grabbing the audio and syncing it up. That’s how it appeared, almost adjoined to structuralist works by the likes of Victor Burgin. And because of the interest I had in the semiotics of film, I wanted to apply what I learned to television. I tried to see what was the most typical or common shot that was used in crime dramas, and it turned out to be the reverse angle. Each of this series of twenty-five image and text panels—ten of which have since been lost—were mounted across the gallery and showed a different reverse angle shot, from crime stories to cop stories. And you would see the image captured, then the reverse angle image that followed it.

The first work that had motion, meaning taking actual television footage, I would say was (A)Drift of Politics “Laverne and Shirley” at The Kitchen in 1978. But because you could not record that imagery at home, the way I got my hands on the footage was finding people in the industry, usually around my age, who late at night felt like, “we’re gonna help her”— usually men—and so, this imagery was then gotten to me. Just to tell you how strange a process this was, with Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman, I did not even own a colour TV at that time. So, when I went into the editing house, the first time I put the footage up to look at it, all of a sudden it was in colour, and then I found that Wonder Woman was wearing red, white, blue and gold. It was shocking—not that it should have been, but it’s just that I had no reference point for the colour. And it simply strengthened what I already felt about it; it made it even more visceral, and it went along with the ideologies I thought I was seeing, but now they’re painted. With that work, by the grace of younger people working in the industry wanting to help, that’s how it was done.

I think what I’m speaking about is relatively young people in their early 20s or mid-20s, maybe questioning what they see first-hand in the industry. And at that age, I was very angry, so you know, they might have that anger too: “I’m making good money, but I want more [out of life].” But its funny because [Walter] Benjamin had talked, much more in relation to radio or newspapers, that it’s here that one might find holes in a medium that itself had become oversaturated. And I think I saw these television programmes as the holes that artists could occupy and then subvert.

Going into the ‘80s, I think a number of artists whom I related to would be looking for different methods to get their statement out. If Barbara Kruger did I Shop Therefore I Am, it could be a painting at the Whitney [Museum], and all of a sudden, it was also a bag that was sold at the Whitney that you’d see in the street. Jenny Holzer is a little bit the same, you know, Abuse of Power Comes As No Surprise ends up on the giant Spectacolor board in Times Square that we had at that time, but it could also be on a T-Shirt. So, I think this idea of trying to get the work inserted into different contexts was a formidable strategy. Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman was shown as a kinescope at The Kitchen, embedding it within the arts.

Beyond that, using a channel like Manhattan Cable D to try and get a slot to programme it at the same time as quote un-quote the “real” Wonder Woman. Or, for example, putting Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman in the window of a hair salon in 1980. I asked the owner of H-Hair Salon de Coiffure, Inc., in SoHo, if I could show it there because they had a monitor. Now, there is not a monitor, screen, Apple Watch, whatever visual device it is, that is not surrounding us, but at that time there was only one store in SoHo that had a monitor, and they would show television programmes while you were getting your haircut. I asked them to turn the monitor located by the storefront window to the street, not towards the patrons. The owner asked me, “What is your work about if we were to show it?” And I did not know what to say, so I said Wonder Woman. And she said, “That’s fantastic, I love Wonder Woman; I’ve been told I look like her.” And she did. And she went for it.

Tiananmen Square was, I believe, the first installation brought into the Kramlich collection, situated at their home in San Francisco. Since then, over the years, they have built another residency in Napa Valley to house their art collection, which is almost a strange museum-like structure. Pam and Richard invited me to their San Francisco house [because] they were thinking of putting Tiananmen Square into what one might call a basement, but it was an entertainment area that was being converted to display video works by Gary Hill, Bill Viola. I did not want to show in that space. But their main staircase led from the entry level up to their more private space, and I said, I’d actually like to wrap that main staircase, so that at every twist and turn we see a different aspect of Tiananmen Square.

It’s five channels, four of which show excerpts of very specific parts of what Tiananmen Square was, culminating with the fifth news channel on a typical-looking TV set from that time. So that became a site-specific version of the work, but it is existent in other configurations, such as at SFMOMA, in its more typical, linear form. Around that time, Richard and Pam had a dinner, and Richard and I loved playing silly intellectual back and forths. He said, “What do you think of the installation?” And I say, “I’m not so sure I like being domesticated!” The point is that video certainly was not part of the arts that had collectors at that moment—although many did have single channel works—and the Kramlichs were one of the first to collect multichannel video. That’s why I call it a kind of domestication of the work.

I mean, right away with (A)Drift of Politics “Laverne and Shirley”, it is broken into three different segments of what you’re seeing or viewing. As you enter the main gallery space, you’re exposed to a kinescope of Laverne and Shirley projected onto a main wall of the gallery. Hanging above the viewer is a monitor tilted downwards with a selection of video footage, and it has subtitles as to what they were saying, but no sound. The film was running at three times slower speed; you couldn’t read as fast as when they were talking on the overhead monitor. The sound was taken out into an adjoining room to be made like a radio play of what they were saying.

I have never figured out my drift, if you could call it that, from architecture into media. I was in architecture when I was very young; I was the only woman who graduated at

Carnegie Mellon University for three consecutive years. It was tough. And the best thing I think I did is, shortly after getting out, was that I went to work for Lawrence Halprin & Associates, in San Francisco. What we designed was not buildings, but consisted of community planning, fountains, landscaping. These things fascinated me: public space and the component it plays in public life. Larry was, I felt, the first environmental architect in the United States.

Around the end of the 80s, I was going into installation, winning the international competition for Rio VideoWall (1989). I didn’t want to enter the competition, but the developer, Ackerman & Co., talked me into it. I wondered how one can show video as a sculptural element, yet not make a video waterfall that repeats all the time. That was the reason [for its] complexity. I thought, with CNN being based in Atlanta, of bringing news into the mall, which you’re probably trying to avoid by shopping, bringing it in through [the image of the shopper], and recording the site before it was torn down because my heart was still in what Halprin had taught me. And that was Rio. It was supposed to be permanent; if it lived a year in situ, that’s amazing.

Journey was originally commissioned by the Miller ICA because they wanted to do a survey of my work—which I believe was to be an honour because I’d gone to the university they were associated with to study architecture. They commissioned a new work, and I was trying to understand, at my age, what that would be. Things for me changed [over time], not only by the vast changes of technology, but the very tools that I use or deal with. They continue to change, also, according to one’s age. Most artists don’t mention their age, but this month [October 2023] as a Scorpio, I will turn 77.

And I think that being this age now, people—or I do—reflect back on life. I believe that people still have embedded, consciously or not, the original components of the younger version of themselves. I was angry; I’m still angry, perhaps in a different way or trying to find different solutions. I was part of the generation that marched on Washington, that marched against the war in Vietnam. So, it is true, especially now, there’s still anger. I have anger toward where we’ve gone, not only in our country, but many other countries as well, and seeing the ruination of the environment that I care so much about.

For a long time, I had this home footage that my father took periodically from when I was born, immediately after World War Two, to when I was [around] 8. What kept coming to me is that Id hidden and cherished these films—was it time to take them out and see if they’re usable? I’m the first child in my family, and was directly looking into the end of that war and this idea of the “American Dream”—even though that was used as a phrase before the war, the re-engagement of it was tremendous at that moment, coming out of World War Two as a supposed victor. So, there was this slightly utopian thing going on: coming back home, building Levittown, doing this and that. I feel that these visions are what I must pass on now, to this and future generations, as an encapsulation of what that was, and in the sense of the actual media.

Home movies were very, very popular in this country after the war, with this technology that had come in with portable handheld cameras. I think that these home movies were made for enjoyment, and maybe looking into the mirror of who we are as a family—the social structure of the family, which eventually is written about by Raymond Williams in terms of how it broke down. But this unity of the idealised family which was seeing itself on the screen: we watched [home movies] within the heart of the home, they became the “fireside chat”. And so that’s why that moment does mean a lot to me. It’s the thing I think I can, and should, pass on.

Many of my works have tried to be tableaus, like Tiananmen Square. You can experience these works in that moment and yet also see its resonances with other moments; Transmission Tower resonates with now, for example. So, with these films that one’s family is making, I thought, let’s also see what television shows I was watching at that time. Do they reveal any of the ideology that was formulated during and after World War Two? For example, there’s Captain Video and His Video Rangers, and it has these specific messages in it. They’re not bad; they actually say, “treat all people equally”, which of course, we’ve never done. But they are directly delivering almost propaganda-like statements to young children in the family at home. I wanted to see what I grew up on, what was planted there, and look back on it. And isn’t it important to leave that image, that tableau, behind for others to examine?